Highlights

- The U.S. is investing $465 million through the DFC to expand Brazil's Serra Verde mine in Goiás state.

- The investment aims to diversify rare earth supply chains and reduce dependence on China's 90% processing monopoly.

- Despite Western financing, Serra Verde's concentrate currently ships to Chinese refineries due to lack of processing infrastructure.

- New U.S. processing facilities are planned by 2028.

- The project is transforming the former asbestos town Minaçu into a hub for ethical rare earth mining.

- Low-impact extraction methods are used to produce 5% of global demand by 2027.

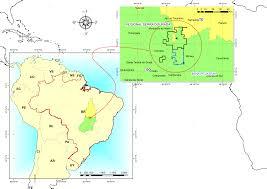

The United States has placed a $465 million strategic wager on a mine in central Brazil—a move meant to loosen China’s iron grip on the global rare earths trade. Through the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (opens in a new tab) (DFC), Washington will fund the expansion of Serra Verde’s Pela Ema project (opens in a new tab) in Goiás state, Brazil’s first large-scale rare earth mine outside Asia. The DFC calls it a step toward “diversified, secure, and sustainable” supply, but there’s an irony the headlines miss: Serra Verde’s early production is already sold—to China.

Table of Contents

A New Front in the Rare Earths Race

Serra Verde is the kind of project U.S. policymakers have dreamed about for years: Western-financed, environmentally modern, and rich in magnet metals — neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium, and terbium — essential for electric vehicles, wind turbines, and defense tech. The ionic-clay deposit allows extraction without explosives or harsh acids, and the company touts renewable power and dry-stacked tailings as proof that mining can be cleaner. With a projected output of 4,800 to 6,500 tons of rare earth oxides by 2027, Serra Verde could eventually supply 5 percent of global demand.

Backed by Denham Capital (opens in a new tab), the Energy & Minerals Group (opens in a new tab), and Vision Blue Resource (opens in a new tab)s (led by ex-Xstrata chief Sir Mick Davis), the mine is a flagship of the U.S.-led Minerals Security Partnership. The DFC’s loan — one of its largest-ever in critical minerals — will fund processing upgrades and refinance debt, signaling Washington’s determination to build a non-Chinese rare-earth ecosystem.

The Paradox Beneath the Promise

Yet the geopolitical picture is more tangled than the press releases suggest. For now, Serra Verde’s concentrate has only one realistic destination: Chinese refineries. Beijing still processes roughly 90 percent of the world’s rare earths and an astonishing 99 percent of the heavy elements that make EV motors and missile systems work. The United States may finance Brazil’s mine, but China still owns the midstream.

It’s a pattern familiar to anyone watching this space. Australia’s Lynas ships semi-processed feedstock to Malaysia; California’s Mountain Pass sends concentrate to China. Until new Western refineries come online — Lynas’s Texas plant and Aclara’s planned U.S. heavy-REE facility by 2028 — even “friendly” ores will flow through China’s hands. DFC’s investment is thus a bet on timing: build the upstream now, and hope the refining infrastructure catches up before Beijing tightens the spigot again.

From Asbestos to Opportunity

For Minaçu, the town nearest Serra Verde, the mine represents redemption. Once an asbestos boomtown, it was left adrift after Brazil banned the toxic mineral in 2017. Now, it's miners’ children who are extracting materials for wind turbines and electric cars instead of lung-scarring fibers. Employment and local revenue are rising, and community relations so far appear cooperative under DFC’s strict social standards. If Serra Verde can maintain that record, it may set a template for ethical rare earth development across the Global South.

The Green Mine Question

Serra Verde markets itself as a “green” mine — low acid use, dry tailings, renewable power — and its backers highlight this as a model for ESG-aligned critical minerals. Still, the DFC has classified the operation as Category A, its highest environmental-risk tier. Open-pit disturbance in Brazil’s Cerrado biome must be managed carefully to avoid biodiversity loss and water pollution. So far, no major incidents have been reported, but oversight remains crucial if the project is to retain its “clean supply” credibility.

A High-Stakes Experiment

Serra Verde is more than a mine; it’s a litmus test for the West’s rare earth strategy. The U.S. is betting that aligning capital, community, and climate goals abroad can counter China’s decades-long industrial head start. If Brazil and its partners build processing capacity before 2030, this $465 million could prove transformative. If not, the ore will keep sailing east — a reminder that digging rocks is easy, but rewiring global value chains is not.

The rare earth game is far from over. Still, for now, Serra Verde is its most revealing move: a mine born of hope, funded by Washington, feeding China, and testing whether the world can ever build a truly independent supply of the metals that power modern life.

© 2025 Rare Earth Exchanges™ – Accelerating Transparency Across the Critical Minerals Supply Chain

0 Comments