Highlights

- First industrial-scale bioleaching trial successfully extracted rare earths from 3,000 tons of ore with 95% recovery in 60 days, achieving 50% higher yields of valuable heavy rare earths compared to conventional ammonium sulfate methods.

- Microbial bioleaching operated at near-neutral pH, resulting in improved soil quality with higher pH, organic matter, and nitrogen content while supporting resilient microbial ecosystems instead of causing acidification and contamination.

- Research by Central South University demonstrates a cleaner alternative to environmentally destructive traditional rare earth mining, offering a viable path for securing critical mineral supply chains without ecosystem damage.

Rare earth elements (REE) sit at the heart of modern technology—from electric vehicle motors and wind turbines to advanced military systems. But extracting them, especially the most valuable heavy rare earth elements (HREEs), has come at a steep environmental cost.

A new study (opens in a new tab) published in Minerals Engineering and funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China and national postdoctoral programs suggests there may finally be a cleaner alternative. In the first-ever industrial-scale trial of its kind according to the authors, researchers led by Xiaoyu Meng (opens in a new tab) with Central South University (opens in a new tab) (CSU) and Key Lab of Biohydrometallurgy of Ministry of Education, both in Changsha, Hunan China demonstrate that in-situ bioleaching—using microbes instead of harsh chemicals—can successfully extract rare earths from ion-adsorption ores while causing far less ecological damage than conventional methods.

Note Dr. Xiaoyu Meng is a rising researcher and Assistant Professor at CSU specializing in Minerals Processing & Bioengineering (opens in a new tab), focusing on REEs extraction, particularly using biohydrometallurgy, a field where CSU is a leader, connected to prominent figures like Professor Guanzhou Qiu.

Table of Contents

The Problem With Traditional Rare Earth Mining

Most heavy rare earths come from ion-adsorption deposits in southern China. For decades, these ores have been mined using ammonium sulfate solutions under acidic conditions, a process that strips rare earth ions from clay minerals. The method works—but at a cost. It has left behind acidified soils, contaminated groundwater, disrupted microbial ecosystems, and environmental damage that can persist for decades. Many media articles have covered the associated damage in Myanmar and the surrounding environments, for example.

As environmental restrictions tighten, this chemical approach is becoming harder to justify—and harder to permit.

Mining With Biology Instead of Chemistry

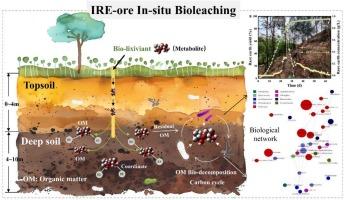

Meng and colleagues, all based in Changsha, the capital of central China’s Hunan province, tested a radically different idea: let microbes do the work. Rather than forcing rare earth ions out through aggressive ion exchange, bioleaching relies on microbial metabolic products that gently bind rare earth elements through complex chemical interactions. The process operates near neutral pH, avoiding the acid shock that devastates soils.

In an industrial trial involving 3,000 tons of ore, the results were striking:

- 95% total rare earth recovery in just 60 days

- Preferential extraction of heavy rare earths, including dysprosium, terbium, and erbium

- Yields of several HREEs were more than 50% higher than those achieved using ammonium sulfate

In other words, the method didn’t just match conventional mining—it outperformed it where it matters most.

What Happened to the Soil?

Just as important as recovery rates was what happened underground. After bioleaching, soils showed higher pH, more organic matter, and improved nitrogen content compared with unmined soil—yet still remained less altered than agricultural land. Far from sterilizing the environment, the process appeared to support microbial life. Advanced DNA sequencing revealed a shift toward bacteria involved in organic matter decomposition and carbon–nitrogen cycling, particularly members of the Clostridia and Proteobacteria groups.

Network analysis showed resilient microbial communities capable of adapting to the added organic inputs from bioleaching.

In short, the soil ecosystem bent—but did not break.

Why This Matters

This study offers the strongest evidence yet that industrial-scale rare earth bioleaching is technically viable and environmentally gentler. For a world racing to secure rare earth supply chains without destroying ecosystems, the implications are profound.

That said, the authors are careful about limitations. The trial was conducted at a single site in southern China, and long-term ecological effects beyond the study window remain unknown. Scaling the technology globally will require site-specific validation, regulatory acceptance, and economic analysis.

Still, the message is clear: rare-earth mining need not be synonymous with environmental harm. By replacing chemical force with biological precision, this research points toward a future where the materials powering clean energy are mined in cleaner ways.

In the global race for critical minerals, microbes may turn out to be unlikely—but essential—allies.

©!-- /wp:paragraph -->

0 Comments